THE LIFE OF THE ARTIST AND THE CREATIVE PROCESS - PART 6

SHANE GUFFOGG: SPANDA

“Everything in life and everything in nature experiences the field of consciousness. This is why we say: Consciousness is all there is.” — Dr. Tony Nader

The simplest, most profound truth may be that consciousness is all there is. It is not material—it is not matter. It is the source, the singularity, from which everything arises. Nothing comes from nothing; consciousness maintains unity while birthing infinite form.

Are we living in an illusion? No—what we experience is very real. But what we perceive as material may be an expression of a deeper field of consciousness.

In Part 5 of this series, Shane Guffogg was completing work for his solo exhibition at the Bovolo Museum during the Venice Biennale. Since then, he has presented solo shows in Los Angeles, Paris, New York, and most recently in Seoul, South Korea. These achievements came through both persistence and surrender—acting with intention while allowing a universal order to unfold.

Yet, nothing could have prepared us for the sudden loss of Patrick Carpentier in May 2024, who passed away before a studio visit with Shane in Los Angeles. Patrick had been instrumental in building connections across Europe. With the help of many—Adam B., Victoria Zhong and Thierry Tessier at Vanities Gallery, Jun Chang in New York, and Seoul—we continued. Shane’s journey has never been a solitary path; it is built on shared vision and support.

In parallel, I began practicing Transcendental Meditation, which helped me understand Shane’s paintings on a deeper level. I began to glimpse the unified field—how Shane, through his paintings, acts as a conduit for something larger than himself.

One painting in particular has taken on central importance: Spanda. Shane has been working on it for over eight months. The title, drawn from Sanskrit, refers to the subtle vibration that animates the universe. When I saw a recent photo of the work, the word that came to me was “Revolutionary.”

Guffogg’s Spanda, 2025 oil on canvas, 84 x 108 inches

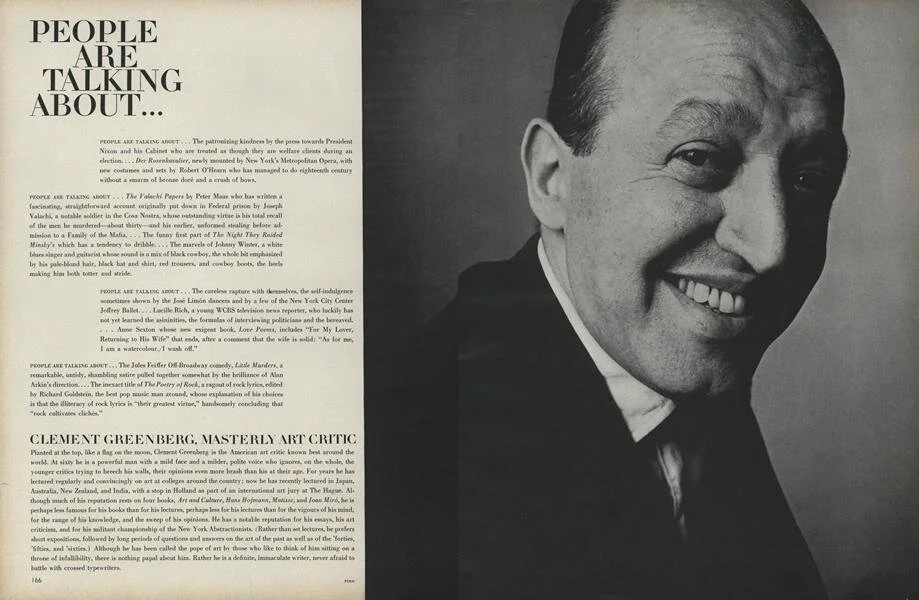

To understand why, it’s helpful to recall Clement Greenberg, who helped define mid-20th century American painting. In his 1961 essay “Modernist Painting,” Greenberg argued that the value of art lies in its formal qualities—line, color, medium-specificity—not in narrative or content. He championed abstraction as a purifying force, moving painting away from illusion.

Shane shares Greenberg’s appreciation for gesture and medium but goes further. His work is not just about form—it is about presence. Spanda is not self-referential; it is metaphysical. It invites us into a unified field where color and form are carriers of consciousness.

“Clement Greenberg’s ideas gave American artists a platform to define themselves outside of European influence. In doing so, he helped launch a uniquely American aesthetic identity.” | Photo credit: public domain

At Shane’s solo exhibition in Paris, quantum physicist David Ash, author of Was Einstein Right?, traveled from Cornwall to see the work. After spending time with Shane, he exclaimed, “You are painting what I am writing about!” The two bonded immediately. Ash later asked to include Shane’s work in his next book as visual counterparts to his theories.

Guffogg’s paintings suggest that consciousness is not within us—it is all around us. The canvas becomes an event in the field of awareness. His ribbons of color are not simply abstract forms—they are transmissions, meditations, and echoes of a larger structure.

Guffogg’s studio in California’s Central Valley—surrounded by crops, orchards, vineyards, and rose gardens—provides a natural rhythm to his process. This setting recalls the American Naturalists of the 19th century, like Frederic Church and George Inness. While Church captured the sublime grandeur of nature, Inness shifted toward a spiritual interpretation, influenced by Swedenborgian mysticism. His later works, veiled in atmosphere, suggested that the visible world was a portal to divine truth.

Like Inness, Guffogg invites contemplation. But instead of depicting landscape, he internalizes it. His gestures, executed without sketches, emerge from a meditative state—each brushstroke an act of listening. His technique is meticulous: sometimes over 100 layers of translucent oil paint build a luminous depth. His ribbons resemble tidal lines in sand, waves of memory, or movements of breath.

Frederic Church Twilight in the Wilderness 1860, oil on canvas, 40 x 64 inches, Cleveland Museum of Art | Photo credit: public domain

DETAIL of Spanda, oil on canvas

George Inness, End of the Day, 1855, oil on canvas, 16.5 x 11.73 inches | Photo credit: public domain

Jackson Pollock, Convergence, 1952, oil on canvas, 93.5 x 155 inches | Photo credit: public domain

Unlike Pollock’s explosive action painting, Guffogg’s motion is inward, slow, and deliberate. He doesn’t paint what he sees—he paints what he senses. He calls these “invisible moments”—evidence of the divine.

Spanda is a culmination of this process. Its red ribbons twist through light and shadow, opening a space of surrender. Viewers often report being transported—drawn into a threshold where sound, color, and light merge. Shane’s synesthesia—the ability to hear color—adds another layer of experience. The painting doesn’t just speak; it sings.

If Greenberg argued for the purity of painting as medium, Guffogg proposes painting as a gateway to the infinite. He doesn’t reject abstraction—he transforms it. His work does not rest in formalism, but in transcendence.

Through Spanda, Guffogg has created not just a painting, but a map—of memory, energy, presence, and the possibility of awakening. It is revolutionary not in political terms, but in how it shifts our perception of what painting can be: a luminous record of consciousness moving through time.

- Victoria Chapman

Los Angeles, May 19, 2025