We continue the dialogue by exploring the work of Vincent van Gogh, Edvard Munch and Paul Cezanne.

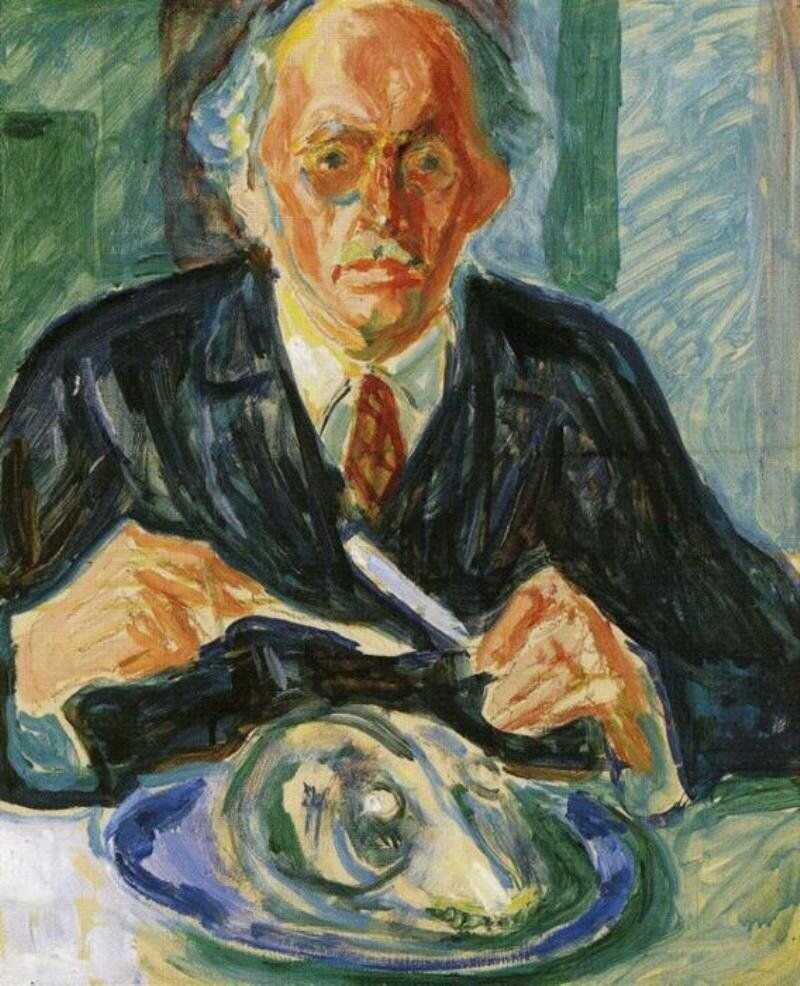

Shane Guffogg, 2018, Fauve Mask Self-Portrait

Oil on canvas board, 14 x 11 in

Shane Guffogg: Self-Portraits, Part 2

(conversation between Victoria Chapman and Shane Guffogg continues)

We continue the dialogue by exploring the work of Vincent van Gogh, Edvard Munch, and Paul Cezanne. We share the developments of why these artists made it their sole purpose to create art.

VC: Vincent Willem van Gogh (1853 – 1890) was an artist whose personal history and legacy is just as famous as his paintings. The son of a pastor, Vincent grew up with core religious and spiritual beliefs that followed him throughout his turbulent life. Floating from one occupation to another, he worked as an art dealer, teacher, missionary and finally found his true calling as an artist. How do you think this played out in van Gogh's art?

Shane Guffogg: That is an interesting question. On one hand, the two occupations of a missionary (or preacher) and an art dealer are polar opposites. However, what would happen if the two were merged into one? Art and religion? That outcome is spirituality, and in van Gogh's case, is manifested through the act of seeing, observing, and ultimately translating his emotional experiences through paint. His mature work reveals his love of the beauty he sees in nature. His objective, I think, was to convince his viewer of the spirit and presence of God. That knowledge or message could create a spiritual awakening, setting his audience on a path of enlightenment. That is the work of a true missionary!

Vincent van Gogh, 1887, Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat

(obverse, The Potatoe Peeler)

Oil on canvas, 16 x 12 1/2 in.

VC: From a young age, Vincent van Gogh made drawings and collected artful objects like bird nests and bird eggs. Do you think this was a means to try to find his place in the outer world, shaping his inner world or psychological state?

Shane Guffogg: The nest and the eggs are such a great metaphor for the quest for the inner and outer worlds to be harmoniously joined. I did a self-portrait back in 1982 and in it, I am approaching the viewer with a tube of red paint and a brush loaded with the same. Above my head is a painting of a table with eggs on it. The eggs should be falling, but they exist in another realm that is happening simultaneously with the one I painted myself in. Starting with the Renaissance, when a student would go to work in the studio of a master, one of their assignments was to draw an egg. An egg is a perfect shape. To represent it properly, the shadows and reflections of light have to be executed accurately in order to create the illusion of a curved object. As an art student at my local college, I drew countless pages of eggs as a way to see (and replicate) light and form. Hence, the eggs in my self-portrait.

Vincent van Gogh 1885, Still Life with Three Birds Nests

Oil on canvas, 13.1 x 19.8 in.

Vincent van Gogh was known to collect, draw and paint birds' nests, he wrote to his brother Theo explaining his fascination

Vincent van Gogh, 1885, Bird's Nests

Shane Guffogg, 1981, Still Life with Eggs

Oil on canvas, 36 x 24 in.

Shane Guffogg, 1982, Self-Portrait (with eggs)

Oil on canvas, 42 x 36 in.

Shane Guffogg, 1981, Broken Eggs

Oil on canvas, 24 x 36 in.

VC: Van Gogh traveled throughout northern Europe, seeking a common understanding. He longed to go to Japan to experience the monastic lifestyle he thought Japanese artists lived but never made the journey. He had high hopes that Arles, France would be his spiritual Japan where he would invite other artists to live and work side-by-side. Do you think the need he had for companionship with contemporaries is common among artists?

Shane Guffogg: Van Gogh was a huge admirer of a Japanese artist who later in life became a Zen monk and lived in a monastery. Van Gogh assumed this was what real artists were supposed to do. However, I will say that being alone in the studio and painting all day can transport an artist all sorts of places. For me, the act of painting conjures up deep memories which then takes my mind on a walk-about. In those moments, having a peer to share ideas with or hear insights from is comforting and even a necessity for some. When I had a studio in Venice Beach (1990 to 1992), I had a neighbor, Ron Griffin, and we would look at each other’s work at the end of each day and talk about it. At one point during that time, Ed Ruscha made a comment to me that we were like Picasso and Braque. Just as those two broke off into their own orbits, that is precisely what happened with Ron and me. The answer to your question is ‘yes’, the companionship of fellow artists is a necessity-- but it varies from artist to artist. I now find myself having the same sort of artistic camaraderie with many creative people, like writers and musicians, as well as artists.

Vincent van Gogh, 1888, Self-Portrait, Dedicated to Paul Gauguin

Oil on canvas, 24 3/16 x 19 13/16 in. Van Gogh was hoping to create a sort of art-monastery in Arles.

VC: Van Gogh was on the go from one place to the next, from Holland to England, back to Holland, onward to France then to Belgium, and then finally back to France. We don’t exactly know who the real Vincent van Gogh was, but we do know he tried to find salvation. What are your thoughts on his never-ending search?

Shane Guffogg: He was searching for his inner truth, but the sad part is that he was looking outside of himself. What he really sought was within him, as it is with all of us. When he started to paint, his inner world became more available and I think towards the end of his life, through his art, he found himself and in that, salvation.

Vincent van Gogh, 1889, Irises

Oil on canvas, 28 x 36 5/8 in. This painting was created a week after entering Saint Paul-de-Mausole asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. The artist felt the act of painting to be the only salvation to his sanity.

Vincent van Gogh,1889, Self-Portrait

Oil on canvas, 26 x 22.8 in

VC: Sadly, Vincent van Gogh never experienced praise for his art during his lifetime; it was only at the end of his life that he began to establish his own aesthetic. The artist painted hundreds of landscapes, cityscapes, portraits, still-lifes and self-portraits. Some of these paintings acted as study guides, exploring techniques and current trends. Many artists painted self-portraits because they didn’t have money to pay for a model. But for van Gogh, self-portraits would seem to take on more meaning and create a statement over time. They began to open a door to his psychological state, as is supported by the connection and correspondence between he and his younger brother, Theo. Vincent wrote some 903 letters during his life and 663 were penned to Theo. Vincent died in 1890 and Theo would be laid to rest next to his brother just a year later. It was Johanna, Theo’s wife, who realized the importance of their relationship and the significance of Vincent’s work, and a massive cataloging took place. Johanna realized Vincent’s letter writing and need to paint was a type of self-preservation, and that like any painter hoping to chart their course to illumination, these paintings tracked his progress. His famous Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear (1889), has symbolic references; an easel in the background that looks like a cross, three Japanese women to the right which may resemble the three graces/muses, Vincent’s protruding bandaged ear … how would you interpret this painting and how did van Gogh’s self-portraits influence you?

Vincent van Gogh, 1889, Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear

Oil on canvas, 24 x 19 in.

Shane Guffogg: That self-portrait is really a portrayal of himself as Christ and the three women in the Japanese print represent three women at the foot of the cross mentioned in the bible. Remember, Van Gogh's father was a preacher and at one point, Vincent also took up the vocation, so he was well-versed in the stories of the bible. Another thing to consider is that the portrayal of his ear would have been influenced by the bullfights that took place in Arles. The matador would cut off the ear of the fallen bull and give it to the prettiest girl he could see in the stands. When Vincent cut off his own ear lobe, he presented it to a prostitute he was in love with. The story is that she fainted upon receiving his bloody gift. The local people of Arles heard about his delusional display of love, and this, compiled with all the other crazy things he was doing, caused the village residents to sign a petition to have him driven out of town!

But van Gogh was trying to paint his own salvation to save himself. All of his self-portraits are a deep look inside his soul. In the self-portrait from September of 1889, he has short hair and he is wearing a gray suit against a background of the same color. The brush strokes in the space around him seem to be telling us that there is an energy around him which only he sees and feels and is now going to reveal to us. His eyes are not looking at us or at his reflection in the mirror. They are staring into a void as if his mind is transfixed on something or someone – unseen. We are walking among his thoughts.

In 1988, I had a run-in with a chop saw and ended up losing my left index finger. I won't go into the shock and despair I felt, but I did grab a canvas the following day, and with my hand all bandaged and in a sling, sat in front of a mirror to paint myself. I needed to see me, in that moment. My life had just hit a bone-jarring bump followed by a huge pothole in the road of life. I was trying to reconnect to myself. The only way I knew how to do so was through paint. Because van Gogh's work is so embedded into our collective psyche, I was thinking of his self-portrait of his bandaged ear. I worked on my own self-portrait daily, beginning the day after my finger was cut off. I remember it was all very painful, both emotionally and physically. On the fourth day, I painted over it completely. I then started from a new beginning and finished it in that sitting. Unfortunately, I didn't think to take photos of each day's work. The painting is unrefined in its paint handling – emotions over technique – but when completed, I was able to see myself.

VC: Is the color of the shirt symbolic?

Shane Guffogg: Absolutely. The red shirt symbolizes the blood, pain and anger I saw and was feeling.

Shane Guffogg, 1988, Self-Portrait

Oil on canvas, 30 x 24 in.

Shane Guffogg, 1988, The Sound not Made by Two Objects Striking

Acrylic and resin on canvas, 12 x 18 in. (diptych)

VC: Similarly, to Vincent van Gogh, Edvard Munch (1863-1944) was another artist deeply invested in the human condition. Munch’s early paintings were often about isolation, loss and existential angst. “Sick Child” (1883), the paintings composition shows his sister who was deathly ill, and his mother, head down, perhaps feeling hopeless. Both of their lives would soon end. Munch created many paintings which tried to analyze his female relationships, “Inger on the Beach” (1889), a portrait of a woman seated on rocks near the water appearing to be reflecting on her existence. From 1892 – 1895, Munch made many paintings of women and men in different states including “Melancholy”, “Anxiety”, “The Day After”, “Woman in Three Stages”, “Jealousy”, and “Puberty.” The last features a wide-eyed young girl sitting naked on a bed with her arms crossed over her legs, resisting her fate. Onward to “Madonna”, a provocative image of a nude woman with open breasts, long dark hair and a red halo and “Vampire”, a woman devouring a man. In the mist of these highly emotional and expressive paintings, Munch created “The Scream” (1893). It appears from my research that the artist was deeply troubled by his own neurosis coupled with heavy alcohol consumption. Instead of seeking professional help, he used his art to work through pain, and like van Gogh, took to frequent writing as an outlet. It seems Munch’s practice of self-portraits began early on. From 1881 until his death, he made paintings portraying himself in a wide variety of situations, from very dark in nature in the early years to more optimistic toward the end of his career. They range from “Self-Portrait with Cigarette”, (1885) the one you mentioned, Shane, where the artist holds a cigarette and stares deeply at the viewer in smoky surroundings and “Self-Portrait in Hell” (1903), a harrowing view of the artist in a hellish background, to the more documentary, “Self-Portrait After Spanish Influenza” (1919), and “Self-Portrait as the Night Wanderer” (1923). It appears that as the artist found notoriety in his career the self-portraits evolved too, as evident in “Self-Portrait with Guardian Angel” (1939), “Self-Portrait with Cods Head” (1940) (a very realistic scene of the artist enjoying a meal of fish) and “Self-Portrait in the Garden Ekely” (1943). Regardless of the subject matter, these self-portraits reveal a deeper sense of his psyche and his quest for a type of enlightenment. We must also remember this was a period of drastic cultural and socioeconomic change-- from the turn of the century to modernity.

As Munch matured, he did many commissions-- some from hospitals. Some historians have said his paintings in his later years lacked the same intensity of his early works. What are your thoughts regarding Edvard Munch’s self-portraits? Do you think an artist needs to be in a state of angst to create great work?

Edvard Munch, 1895, Self-Portrait with a Cigarette

Oil on canvas, 43.5 x 33.6 in.

Edvard Munch, 1894-5, Madonna

Oil on canvas, 35.8 x 27.8 in.

Edvard Munch, 1940, Self-Portrait with Cod Head

Shane Guffogg: The reality is that everyone has some level of anxiety occurring throughout their life... some days being better than others. Munch's paintings were his way of confronting this and his self-portraits are more emotionally autobiographical because he is showing us the specific cause of his anxiety or contentment. In his self-portrait in hell, his facial features are nondescript except for his eyes staring out at us. His body is yellow, reflecting the colors of the fire is burning around him, and unlike van Gogh, whose paint was applied with thick and direct brushstrokes, Munch painted with loose brushstrokes and thinned paint with turpentine. The difference for me is van Gogh's thick surfaces becomes a physical representation of what he painted, whereas Munch's washes of thin paint are more ghostly, haunting, and ethereal. They speak of a psychological state. Hence, Munch is considered an expressionist. The Scream is the ultimate example of his work directly speaking to what I am forever stating about the role of the artist – that the artist is a shaman whose job is to go to the spirit world and bring back their findings to help tribe members (society) through whatever is ailing them. Van Gogh and Munch did just that. Their findings, which are expressed through their art and writings, are there for all of us to experience what it means to have joy or anxiety, to suffer loss, and the pain that follows. Their art is comforting in a way because we realize we are not the only one who is grappling with our humanity.

Edvard Munch, 1903, Self-Portrait in Hell

Oil on canvas, 32 x 25.5 in.

VC: Paul Cezanne (1839 – 1906), deserves a great deal of recognition for his contributions to the history of painting. Although this discussion is about self-portraiture, I can’t escape mentioning Cezanne and his innovations. The artist was known as the father of modern art and laid down the groundwork for cubism. When I think of Cezanne’s paintings, I see objects on a table-- sensually placed fruit. Beyond their poetic compositions, there is something more – the color and light reveal a vitality that beckons us to lean over and touch the fruit. I have listened to recorded lectures where art historians proclaim these as seductive and almost erotic compositions, where they’ve remarked that this is where Cezanne’s intimacy begins and ends.

As we discussed earlier, the release of inner turmoil must land somewhere. I was surprised to learned Cezanne’s early work was quite dark. Through watching a variety of documentaries, I learned the artist struggled with his own personal demons including isolation, lack of intimacy and struggles with acceptance. In the early stages of his career, he made paintings about nakedness, rape and murder. Cezanne was from Aix-en-Provence, and like many of his contemporaries, the goal was to go to Paris, explore art, meet other artists, and experience Parisian life. As his visits to Paris began to lengthen over the years, Cezanne visited the Louvre as often as possible and longed to learn from the Old Masters. He did this by teaching himself to copy their paintings, thinking a connection of sorts may be found. He copied works by Titian and Peter Paul Rubens. Cezanne also admired the work of Eugene Delacroix and Gustave Courbet.

Shane, you have also seen the value in the act of copying paintings, and in your case, as we just explored, you even copied yourself into a painting. What kind of things does an artist learn from paying this homage?

Paul Cezanne, 1867, The Abduction

Oil on canvas, 66 x 34 in.

Paul Cezanne, 1880-1, Self-Portrait

Oil on canvas, 13 x 10 in.

Paul Cezanne, 1879-80, Still Life with Fruit Dish

Oil on canvas, 18 1/4 x 21 1/2 in.

Shane Guffogg: Great question. I think we all need a place to start, and art history is like walking through an endless forest with countless trees, each tree representing an artist of the past. I liked to study these trees – the way they grew, the amount of shade they provided, their beauty – and gathered seeds of my favorite trees along the way. Then, after this long metaphorical journey, I emerged onto an open meadow and claimed it as my own, planting those seeds and tending to them so their growth is pleasing to me. And from the new crop of trees, I built a home and have a shelter that further allows me to contemplate the beauty I am surrounded with. That is how I studied the old masters. Art history is an ongoing conversation from one artist to the next, one generation to the next. One generation may reject what an artist from the previous generation did, others may embrace it and add to it. Look at Picasso for instance. He copied many old masters but came to a point of needing to reject that because the old way of seeing wasn't in sync with the new industrial age, filled with machines and new sounds and a different way of life. It was because Picasso had such a strong foundation in art history and could paint anything that he had the ability and dare I say audacity, to reinvent the wheel. Then we look at Monet and his late works of the waterlilies and how the American abstract artists saw what he was doing and added to his “conversation.” When I hear someone say they have been to Paris or Egypt because they did a virtual tour, I shake my head, because this may be their reality, but it isn't real. A virtual tour doesn't allow a person to immerse the senses, to smell or hear those places at that moment. Nor does it allow any person to understand a sense of the space unless they are standing in it. I feel the same about painting. Just sitting at your computer or flipping through a book is not going to give the same information on how and why an artist made a painting as it would to try and copy the painting. Feeling the movement of the brush strokes and experiencing how colors blend and create space in front of your eyes is like magic. It cannot be experienced any other way except by doing.

Paul Cezanne, 1865, Still-Life with Bread and Eggs

Oil on canvas, 23 x 29 in.

Paul Cezanne, 1870, Pastoral or Idylll

Oil on canvas, 25 x 31 in.

VC: Later Cezanne would meet Pierre Monet and much later Camille Pissarro would become his mentor and guide. During his second visit to Paris in 1863, his work was included in the Salon des Refusés, which is literally what the title exclaims-- he was in an exhibition of works refused by the jury of the Paris Salon. From the years 1864-69 Cezanne would continually be rejected from the Paris Salon. It would be easy to understand through the history of Cezanne’s work why he would return to the countryside to paint landscapes, still-life, family, and self-portraits. What is most fascinating about Cezanne returns me back to his beautiful still-lifes and landscapes, as he treats color in a very new and innovative way. These combinations were unique --different than other artists of the time. He would often lay blue next to green, keeping the layering of paint to a minimum, producing emotional compositions that would enter his self-portraits.

You have created so many self-portraits in different styles and techniques. How has this come about? What are you exploring?

Shane Guffogg: Being a lifelong student of art history, I understand the power of certain images, techniques, and styles. And, living in this Post-post modernist era, I can safely say that all of art history is really there for me to pick and choose from, like the metaphor of the trees, and use again in my own meadow... so to speak. My use of different styles and periods are never really pure (how can they be since I am living in a different era?) Instead, they are more of a fusion of styles, times, artists, and my own emotions.

VC: There is very little known about Cezanne, but we do know he preferred living and working in the smaller provincial towns like Aix to the busy streets of Paris. In these smaller towns, he would create the most alluring landscapes and light engagement. Cezanne did not try to be anything more than this. In 1895, at the age of 56 he received his first solo exhibition in Paris, when Ambroise Vollard (an art dealer), found his work at a store where artists traded paintings for art supplies. This finding led to a solo exhibition in Paris of 150 paintings which Cezanne choose not to attend. Up until that time, his work was still scrutinized by the locals around him.

Have you ever felt like you were stuck? What did you do to work through it?

There must be highs and lows -- how do you keep an even keel so that you can continue to work and reach the next level of success?

Shane Guffogg, 2018, The Watchers

Oil on canvas board, 18 x 14 in.

Shane Guffogg, 1983, Self-Portrait

Oil on canvas, 24 x 18 in.

Shane Guffogg: Feeling stuck is like a recurring ringing in my ears – it happens often. When I first started feeling “stuck” which I think was around 20, I switched gears, changed mediums, and purposely lost myself in making music, which resulted in an album. I recall feeling stuck while at Cal Arts because there, we all had to know what we were doing before we were doing it. That is like playing chess with yourself in your head. As the years went on and this occasional sinking feeling of doubt would creep in, I realized it is part of my process and that I had to learn to dance with my demons before they danced with me. Now, if that stuck feeling pops up, I switch to writing or playing music, or going for a long walk. Whatever it takes to change my immediate thought patterns. Questioning your work is important and it will often slip into self-doubt, but that too is important. There has to be an ability to honestly critique your own work. Writing helps me in that process since I create from a very subconscious place and then I can consciously think about it and try to make sense of it. That is what works for me. Everyone will have their own process, but it is important to realize that there will always be hills and valleys-- each gives a different perspective.

VC: It seems Cezanne never escaped from painting nature. I once read that the happiest time of his life was bathing in the river with his childhood friend, Emile Zola, [Zola would become one of France’s most important writers]. Even when the two did not speak (Zola wrote a scathing passage about Cezanne in one of his books) the artist continued to recount the imagery of bathing. From 1890-6, Cezanne made many paintings of bathers. These paintings are quite mysterious and critics say they lack the emotional impulse of his landscapes and other still life works. There is an awkwardness to his nude subjects, with minimal facial expressions and seemingly distorted bodies. Over time, we would all see these as masterpieces. Matisse and Picasso would be inspired by Cezanne’s bather paintings and would interpret their own versions with such works as, Bonheur de Vivre, (1905-6) by Henri Matisse and Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) by Pablo Picasso.

What do you think about artists making anatomically correct paintings versus ones which are not? Abstraction was kind of born of the transition from realism (the expression of a thing) to the impression (what the viewer might feel or think.) This somehow asks our brain to translate and provide our own conclusions. Clearly, most people would agree that Cezanne’s bather paintings are amazing works of art. Why, then, are art critics discounting the works saying they are awkward when the viewer feels the beauty and senses the light?

Paul Cezanne, 1899-1904, Bathers

Oil on canvas, 20 x 24 in.

Henri Matisse, 1905-6, Bonheur de Vivre

Oil on canvas, 69.5 x 94.75 in.

Pablo Picasso, 1907, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon

Oil on canvas, 8 x 7'8 feet

Shane Guffogg: Painting realistically versus distorting the figure is at this time, a matter of choice based on what needs to be expressed. Before photography, that was a different situation. Now it is easy to paint with all the right proportions because an artist can just use an opaque projector and trace the image out. A lot of artists do that but that, for me, falls into the category of having a concrete preconceived idea and the painting is merely executed versus being in the moment and following an impulse. My work is a combination of the two because the impulse is what starts the painting and that first abstract moment becomes my subject. I then spend weeks or months painting into that initial moment as if it is a real subject. Back to Cezanne, we know he was not a social person and preferred to be alone. He couldn't take any form of criticism. What this all means is that he painted purely for himself with zero regard for the art world because he wasn't a part of it. What freedom he had! The bathers, of which I have seen many around the world in different museums, are more ghostly than real. They are memories he needed to revisit for his own well-being. The still lifes are present and almost tangible. They are not thoughts as much as his pure observations. The same is true for his recurring painting of Mont Saint Victoire. His brush strokes deconstruct the picture plane, revealing the substructure, almost like when you go to a movie set which on one side looks like a real living room wall, and as you walk around them the wooden structures these walls are painted on are revealed. Cezanne shows us both sides simultaneously, and he gives us clues by showing two or three different perspectives of his still life setting all at the same time. The paintings are too well painted and thought out for this to have been a mistake. He knew what he was doing and since he didn't have to answer for it, he had freedom. Maybe it occurred because he moved his chair from day to day and was looking at the table with fruit from different points of view? His still lifes are the most structured of all his work. The landscapes, bathers, and even his self-portraits are more ethereal.

Paul Cezanne, 1887, Mount Saint Victoire with a Large Pine

Oil on canvas, 24 x 36 in.

VC: I learned that later in Cezanne’s career he came to terms with his morality and started to make still life paintings of skulls,. This again seemed to be a natural path to follow; exploring his own rhythms of life including mortality. Thinking about death, reflecting on living, understanding the end. Cezanne worked diligently throughout his entire career, dedicating himself to painting, understanding light and realizing the value of color. In his compositions, Cezanne made a claim that as an artist one would not have to chase after their career, but rather exist and explore the world around him based on his own need to be understood.

What do you think an artist’s career should be grounded in?

Shane Guffogg: That is an easy one. Their personal truth.

Paul Cezanne, 1875, Self-Portrait

Oil on canvas, 25 x 21 in.

VC: While Cezanne preferred to spend most his life in deeper forms of isolation commenting on solitude, he was witness to the landscapes around him. I think this served him well -- to have deeper discoveries into his own meaning of life and the purpose of art as it served him. His ultimate legacy would remain for us to follow.

I didn’t always understand the depth of Cezanne’s work. I typically saw him as this great artist but didn’t know why. Through my research I learned to understand his own personal depths … his fear of intimacy, need for isolation, his rejection from the art world, and public scrutiny. I am starting to see how each artist’s work is a type of self-portrait even if it isn’t a ‘self-portrait’, per se. As one thinks and feels their way through the composition, we are getting in touch with the artist’s truer sense of what they are trying to share through the vehicle of art.

What do you have to say about the artist and self-portraiture when the painting isn’t necessarily a self-portrait?

Shane Guffogg: I think every painting an artist makes is in some way or another a self-portrait. The choices of subject, shapes, forms, and colors all speak to who that artist is and what the artist's life experiences have been, which goes back to my other answer. It all adds up to their personal truth!

Shane Guffogg, 1981, Push and Pull

Oil on canvas, 48 x 48 in.

Shane Guffogg, 1983, Self-Portrait with Primary Colors

Pencil and acrylic on paper, 23 3/4 x 18 in.

Shane Guffogg, 1981, Self-Portrait with Rembrandt

Oil on canvas, 48 x 72 in.

VC: Some of your self-portraits are landscapes or still-life paintings; the viewer is indeed witness to your portrait within the composition.

Can we talk about this more? Why are you compelled to paint in such a manner instead of doing a straight-forward self-portrait from a mirror?

I know it’s a huge subject as he is such an important figure and radicalizer-- changing the way we see early forms of cubism in a sort of ‘fore-shadowing’ effect for others to carry the baton into modernism, but what do you have to say about Cezanne’s contributions to the history of art?

Shane Guffogg: I have been making self-portraits, very quietly, for the past 40 years. It is a way for me to see myself in a more direct way. And in so doing, I hope to have a better understanding of my life and why I do what I do. A couple of years ago, there was yet another mass shooting and it was plastered all over the news. The shock of these events never dims for me. It seems some just become numb to it all. The talking heads talk on TV, the politicians expressing regret, offering suggestions on ways to fix these ongoing problems. On that particular day a couple of years ago, I was in my studio working on an “abstract painting” and the news came out about the shooting. I felt that I just couldn't take it for another moment – this news was a tipping point for me. I decided I needed a way to look out at the world but from a safe place. This brought up the idea of wearing a mask, which most cultures around the world participate in, as we do on Halloween. Masks were, and in some cases still are, a way to ward off evil spirits. So, I started painting masks that I would peer out from. Over the past two years, the masks evolved as the different world and personal events occurred. Art history became a fertile place to explore for these masks, which gives me the freedom to, once again, try on another artist's shoes, so to speak.

Cezanne was one of many artists who took a different path through the woods and found a different place to create what he saw. His truth resonated in a way that began a new era. He was the one in-tune with the changes happening in the western world as the camera and then film was introduced, and trains were now moving across the landscape-- soon to be followed by cars. His work takes what the Impressionist started with, which was the idea of capturing the impression of a moment and pulling that moment from one century into the next. His paintings, with the brushstrokes that seemingly made nature into a visual mathematical equation, created a portal for Picasso, Braque, and Matisse to walk through.

There are no right ways to go about making art, but there are many wrong ways. We intuitively recognize the right ways and that is what helps to change the way we see the world.

Shane Guffogg, 2018, Grey Mask Self-Portrait

Oil on canvas board, 14 x 11 in.

Stay tuned for more conversations

Victoria Chapman

Studio Manager

A very special thanks to Monica Edwards for editing.

Note: all images shown in this email are (fair use) public domain