The discussion continues with Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso

Shane Guffogg, Cubist Eye Self-Portrait, 2018

Shane Guffogg: Self-Portraits, Part 3

(conversation between Victoria Chapman and Shane Guffogg continues)

In Part 3, we enter the worlds of Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso. I spent time researching the artists and some of their life experiences that shaped many compositions and self-portraits. I had more questions for Shane Guffogg, which he carefully shared his personal takes on, giving me a deeper understanding. This led me to draw curious parallels between the artists of the past and Guffogg, parallels that reveal more and more about his work.

V.C: Henri Matisse (1869-1954) was another artist that advanced modern art, but not without hardship. It took until almost the end of his career for the public to understand his work. Matisse also created self-portraits, utilizing different styles and mediums: etchings, paintings, simplified line drawings, etc. I learned from my research that Matisse valued painting the relationships between objects rather than just the objects themselves. He’s known for his still lifes and portraits. He eventually made paper cut-outs, which would become the most-known works of his career. The artist was also known for painting his own spirit into his works; not his recognizable face, but his presence within the scenes he painted. He not only recreated the world around him in a dazzling array of colors and lines, but he also painted a life force within it. In the Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence, which is decorated in colored stained glass and black line drawings, Matisse displays his version of Stations of the Cross. The colored stained glass cascades on the visitor, sharing space within the white walls – color from the light is the environment.

Henri Matisse making art for Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence

His painting The Red Studio (1911) is another example of this. One gets a sense of the artist’s studio, saturated in the heightened emotion produced by the color red. The hands of the grandfather clock are missing; what is the artist saying here? The viewer enters the painting from where the artist stands, soaking up what Matisse sees, feels, and desires.

What is your take on this painting and Matisse’s spirit within his works? You have created many self-portraits, but like Matisse you have painted not your face, but your presence, commenting on history, politics, and your personal life. Are you willing to share with me what this is all about?

Henri Matisse, Self-Portrait in a Striped T-Shirt. 1906, oil on canvas, 22 x 18 in.

Henri Matisse, The Red Studio, 1911, oil on canvas, 71.25 x 86.25 in.

Shane Guffogg: I love what you are getting at here. Basically what you are saying is that Matisse was painting the essence of life, that invisible energy that gives rise to thought and creation. We take it for granted because we are it, so it is not something we necessarily think about. But when we lose a family pet, or worse, a family member or loved one, the invisible life force leaves and we see its absence. So, back to your question. Here are my thoughts – Matisse's work, such as The Red Studio, is really a psychological portal that we can enter, bringing us closer to our own inner-self. That is what we call invisible energy. I think another word that would make more sense to people is soul. Regardless, art is the conduit to bring us back to ourselves.

I think of art history as an ongoing conversation between generations. When I look back to the ‘80s and the idea of appropriation that was so prevalent then, I think about that time in history like a train that got derailed in a desert. The train was carrying artifacts from throughout history and they got scattered across the desert landscape. The appropriation that took place in the ‘80s was, to my way of thinking, a group of artists picking up bits and pieces that they found interesting and reusing them to try and make something new. My self-portraits are a different animal from what the ‘80s appropriation was about – my self-portraits are a way for me to see myself, from an emotional and psychological perspective. According to the art critics and some of the artists that popped up in the 80s, their work was spiritually bankrupt, which was a reflection of the excess money and lack of humanity of that time. The problem I felt then and continue to feel today about a lot of that work, is they are dead on arrival due to their lack of real investigation into the human condition. Matisse's works are filled with an indescribable energy that shimmers through the colors he used.

Shane Guffogg, Fractured, 2019, oil on canvas board, 12 x 9 in.

Shane Guffogg. Lovers, 1983, oil on canvas, 36 x 72 in.

Shane Guffogg, Hollywood Son, 2020, oil on canvas board, 12 x 9 in.

VC: Is the artist ever separate from his artwork?

Shane Guffogg: I think Matisse was absolutely seeking something very personal, which was a new way to see the world that reflected the changes that were happening via technology and science. Technology changed the way people moved from point A to point B and the world began to become more accessible. Matisse traveled to Morocco and was heavily influenced by their culture and the Islamic architecture and colors. His work spoke of a new era of globalization. If the artist is making the work then it can't help but be a direct extension of their truest self. If, on the other hand, the “artist” has a design and production team cranking out the works, then, no, it is not a direct extension of the artist, and from where I stand, it is not really art but more of an artifact that is designed to be a commodity.

VC: A friend recently mentioned to me why Leonardo da Vinci was such an extraordinary artist, and they felt it was because Leonardo was successful in leaving a sense of personal energy within his paintings and drawings. What do you think? Do you feel this is also the case for Matisse? Is color his vehicle?

Shane Guffogg: Your question is something I have pondered over and over. I can say something that sounds like I am sprinkling fairy dust around, as in yes, there is a magic that is beyond words in great art. But realistically, or I should say, scientifically, the idea of energy is just that, an idea. Our thoughts are energy and our reality is the manifestation of energy into a physical form. We also know sound is energy as are colors. Colors vibrate and that changes the way we see. When an artist thinks and creates, their energy of thought is manifesting into an artistic form, like painting. And the colors vibrate with the artist's thoughts embedded in the work. I think there is a transfer of emotions and ideas from the artist into the art, whether it be painting, drawing, music, etc.

Henri Matisse, Self-Portrait, 1918, oil on canvas, 65 x 54 in.

VC: We cannot talk about Matisse without mentioning Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), as both artists were introduced to the public by art collectors Leo and Gertrude Stein, who collected their works. In the beginning, Picasso and Matisse were rivals, working against one another in an attempt to take over the global art stage. Both artists made a huge impact on modern art in the 20th century, both their major works and their self-portraits. When I look at a painting by Picasso, I also look at his photographic portrait and facial features to guide me through it. I get lost in his dark black eyes, searching to find meaning in the depths of his paintings. I question the imagery posed – centaurs, doves, women crying, chaos, sex, order, cubism, and more. Picasso’s journey in art and the paintings and drawings he made, from my point of view, feel autobiographical. Unlike Cezanne, who explored the outside world to find solace in his art, Picasso seemed to use relationships, especially with women, to find meaning in his own feelings and perhaps the bigger questions in life and how he might fit in.

With that aside, and looking at the earlier Picasso before he became the great Picasso he is today, you share many parallels. You both were self-taught artists from a very young age. Although Picasso had his artistic father to watch over him, and you were not born into an artistic family. Picasso said he would only go to school if he could draw. Similarly, you were discovered at school by a teacher who realized your gift. Tell me how your life began as a child in art and the people that watched over you to be sure you were getting your time to draw.

Pablo Picasso, Self-Portraits, left:18 years old, and right: 25 years old

Pablo Picasso, Is the artist ever separate from his artwork?

SG: Ah, the beginning of the beginning. My earliest memories are drawing with my mother. I remember very clearly making scribbles, like any kid would do, but I would ask my mom what I had written. She would then find shapes that were close to looking like letters. I like to think I was swimming in my subconscious mind, untethered by the conforms of formal education. When I started kindergarten, I felt it was a disruption to my normal routine of drawing. I wasn't really all that interested in school and especially not the homework, but I trudged through it, always hoping that there would be a drawing assignment. In first grade we had a drawing assignment, a self-portrait in a shower or bath. I was always fascinated by the patterns the tiles made in the shower so I chose that as my place. I couldn't figure out how I was going to draw myself behind the shower curtain, so I pulled the curtain back and drew myself nude, staring straight out. Mind you the drawing was crude, as in, just a step or two above a stick figure. But there I was, anatomically correct with every tile on the shower wall drawn with great care. My parents saw the drawing and they thought it was good. When I turned it in, I saw that all the other kids drew themselves just peeking over the bathtub or around the shower curtain. The kids started making fun of my drawing, as kids do, and everyone was convinced I would be in big trouble. Sure enough, when the teacher, Mrs. Cowper, came to mine, she stood up and told the class she would be right back and walked out of the room with my drawing. She came back and class resumed, but then the intercom speaker in the room began to crackle followed by the principal asking Mrs. Cowper to bring Shane Guffogg to his office. My heart sank as all the kids started whispering about how much trouble I was in. When I arrived at his office, he asked me to take a seat and then held up my full frontal nude drawing asking if I had made this? I said yes, thinking it was the right thing to do. Then he asked who helped me with it? My parents? A sibling? A relative? Neighbor? No, it was all me, there was nobody else to blame. He saw I was afraid and reassured me I was not in trouble. Then he said that he wanted to have my parents come in for a meeting. That was arranged and I remember my dad was mad because he had to take time off of work. Anyway, we went in for the meeting, and my teacher was also there. My parents confirmed that I did the self-portrait by myself without any help and my dad complained that they couldn't get me to stop drawing and just sit with them to watch TV like a normal family.

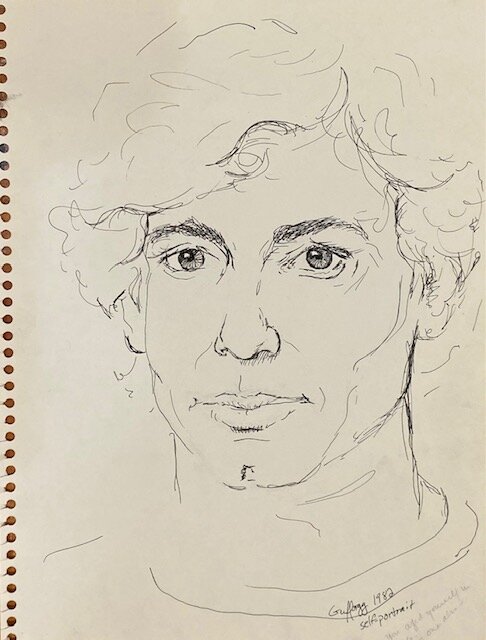

Shane Guffogg, Self-Portrait, 1982, ink on paper, 12 x 9 in.

Shane Guffogg, Self-Portrait, 1982, oil on canvas, 36 x 32 in.

The teacher asked what they were doing for me at home because they had a very sensitive and gifted child, to which my parents replied with a look of astonishment, (nothing). Cut to, my teacher came for dinner every week, mainly to help guide my parents. From that moment forward, I was the classroom artist. And in second grade, our teacher had to leave due to health issues and the permanent substitute was a local art instructor. Most of the homework assignments involved drawing so I was in my element. But I was also torn because I wanted to play sports like everyone else, which I did, but I was labeled as this artist type kid, and the two don't mix.

When I got to high school, I promised my mom I would take an art class. One day we had a drawing assignment that I was not interested in doing, so I drew the back of the head of the girl in front of me, who had beautiful long wavy hair. The teacher saw what I was doing, and at the end of the class took my drawing saying I hadn't done the assignment. But what he did with the drawing was had it matted and put it in a local art show, without telling me, and it won first prize. My sophomore year of high school, we got a new art teacher who was fresh out of college. After 2 weeks, he asked me to come into his office and admitted he didn't quite know what to do with me and asked for any suggestions. I asked if he could create a special curriculum for me that would include art history and give me artists to look up and research. I also suggested I create my own list of art assignments and he critiqued them. It was a win-win for both of us. I still have all those drawings from back then.

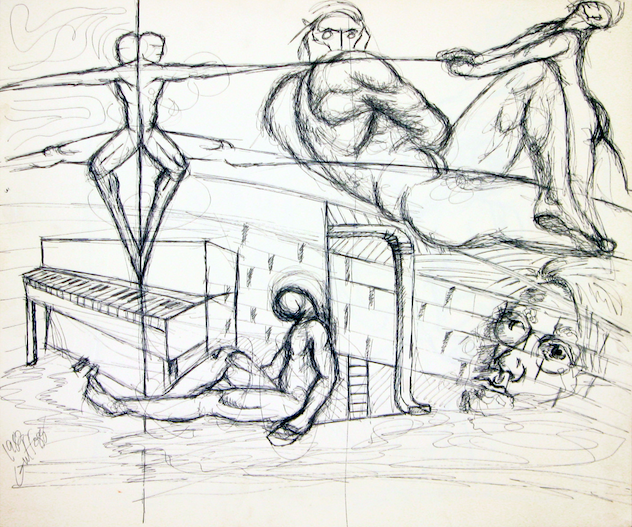

Shane Guffogg, Self-Portrait with Piano, 1983, ink on paper, 10 x 14 in.

VC: Picasso had to get away from his father to formulate his own career-path; he even took on his mother’s surname. It was clear that his father was disappointed with his son’s decisions of entering a bohemian life and not taking a more conservative and traditional role in his career as an artist. Picasso’s father felt his son could paint traditional scenes and portraits and show in the finest museums alongside Goya and Valasquez. Instead, Picasso created his own path on how and what he was going to paint. Share with me how you had to leave your family to begin a life in the arts and all the sacrifices you took along the way to follow your own path as an individual during your lifetime.

Shane Guffogg: Well that is a big question to answer. As you know I took off for Europe the day after graduating high school with the goal of standing in front of as many great works of art that I could. I was fairly successful and it had a huge impact on me. When I returned home I enrolled in a local junior college with a major in music and minor in art. After a semester I realized music theory was not for me (it was too rigid) so I dropped music and changed my major to art. My parents were getting nervous about me pursuing art as a career and I remember one evening I was in my room drawing and my dad knocked on the door saying he needed to talk to me. He asked what I wanted to do with my life and I announced that I wanted to be an artist. His head dropped and he let out a sigh of disappointment. He said that he and my mother thought I had talent but they couldn't stand by and watch me be a starving artist. I assured them I would not starve. My optimism was not enough to sway them and they demanded that they have a chance to meet with and talk to my art teacher at college. After a few days of asking and arguing with my teacher, he reluctantly agreed. My parents and I met in my teacher’s little office on campus and the clashing of egos began. My teacher wouldn't say if I would be able to make a living at art nor would he say if I had the right stuff to make it in the art world. He gave his reasons, which were basically he was not a prophet or fortune-teller and there were too many variables to know. The back and forth went on for an hour until finally, my teacher said that if I went to work in a gas station, within a year, I would probably own it. That was enough of an endorsement for my parents and the meeting was over.

From there I transferred to Cal Arts and did a semester in New York working for an artist who was well-known at the time. I really didn't know anything about the art world or what a day in the life of an artist was like. The best way I could think of to get a crash course on the realities of being an artist was to work for one.

And yes, there are many sacrifices along the way. When I had to choose between buying groceries or the tube of red cadmium to make what I thought was going to be a great painting, I would choose the paint. And of course, that plays into relationships as well. Living the life of an artist, holed up in the studio and trying to figure out the unspoken language of the universe looks romantic from the outside, but it comes at a cost. And that cost wears thin on love interests and personal relationships.

Shane Guffogg, 2019, Untitled Mask, 2019-5, oil on canvas board, 11 x 14 in

VC: Picasso copied many of the Old Masters’ works as well as the self-portraits of other artists. John Richardson, the famous friend, and biographer of Picasso, said the artist ‘cannibalized’ masterworks by Rembrandt, Goya, Matisse, and more to define his own place in history. I would not say you ‘cannibalize’ master paintings, but you have copied many paintings that share your perspective. Why has this been so important?

Shane Guffogg: I think the best way to learn what an artist was thinking is to walk in their shoes, so to speak. I have learned so much about painting and the reasons why an artist creates, by taking on their style or even going so far as to copy a particular painting. When I appropriate styles for my self-portraits, I also learn a lot about a particular movement, like Cubism. When you gave me a book on Cubism a couple of years ago, I was reminded and so taken by the early cubist paintings of Picasso and Braque. I ended up making two self-portraits in a cubist style with my left eye peering through. I am literally looking through a cubist lens. But what I had taken for granted about cubism, the multi POVs that collapse the 3-dimensional illusionary space into a 2-dimensional plane, was something that was not so easy to do! They quite literally developed a new way to see and think. How else would I know unless I try it on for size?

VC: “La Vie” is a painting Picasso did of his friend that killed himself over a love triangle between the artist, himself, and his girlfriend. Picasso was recovering on some level from his friend’s death when he created the painting. This painting was recently scanned and it was discovered that Picasso had painted a self-portrait underneath the surface. What do you have to say about this?

Shane Guffogg: Two things. One is maybe he intended for it to be a self-portrait but felt it would bring him bad luck since he was very superstitious. Or, he wasn't happy with the self-portrait and not having another canvas around decided to paint over it and start something else. I have done that many times – I lose my connection with the painting and just paint over it and start fresh!

Pablo Picasso, La Vie, 1903, oil on canvas, 76 x 50 in.

It is rumored that Picasso's portrait is under this painting

VC: Early on Picasso began modifying the copies he was making of Old Master works, adding his own spin to them. Still being unsatisfied he went on to develop other movements in art to fulfill his vision. Cubism was one of these movements. When he was working on Gertrude Stein’s portrait between 1905 and ‘06, it took 90 sessions – not because Picasso could not paint the famous writer and art collector, but because he wanted to portray her essence and her future wisdom. He was inspired by early religious statuary and African primitive sculpture to capture that sense of depth within simplicity. Can you please explain to me more about what he was trying to capture in the portrait of Stein?

Shane Guffogg: Picasso was taken aback by Gertrude Stein's brashness and the fact that she was a lesbian and made no apologies for it. She was a different type of woman than he had ever encountered and he didn't quite know how to show that. There was a museum show of African tribal art and Picasso realized their art was more direct and pure. In comparison to western art, which would show images of primitive people or rituals, this African work wasn't an image of something, it was the thing itself. He found that to be very powerful and started to figure out how to put that into his own work. These bold and angular lines found their way into his work, eventually becoming cubism.

Pablo Picasso, Gertrude Stein, 1905-6, oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 32 in.

Inside Gertrude Stein's home, see her portrait middle right

VC: Picasso made many self-portraits in a variety of mediums. I really don’t know what to say about them. His eyes always seem to take over the composition, leaving the viewer wondering who the artist is behind the genius. There is a desire to understand the human condition – a sort of wondering, wanting, feeling, or searching. When we look at his entire body of work and the portraits he painted, they were influenced by the partners he chose to occupy his thoughts, they are related to the great existential question.

The self-portrait, “Yo, Picasso” (I, Picasso), 1901, oil on canvas, is a unique one. This painting was created in May of 1901 during Picasso’s blue period, which was inspired by his friend Carlos Casagemas’ suicide. The painting was reminiscent of Vincent van Gogh’s portraits and even Raphael’s portrait of Castiglione. The colors in “Yo, Picasso” begin to fade into each other. Picasso himself is looking forward, rather than back. His face is slightly turned to the side, his eyes peering, watching. He dons a white shirt with an orange scarf; his hair thick and his expression is candid. Picasso was 19 years old at the time and had come to Paris. It is believed that this was the year that Picasso became Picasso, leaving his father’s surname ‘Ruiz’ behind and taking his mother’s, effectively rejecting the world his father had carefully laid out for him. This portrait is, therefore, a true declaration of self. Picasso had other plans; traveling to experience Parisian life was one of them. In Paris, the artist realized he could be free to pursue the life that mattered to him rather than the conservative life his father wanted for him. This painting, “Yo, Picasso,” is a testimony to that moment. A moment for him to finally set out and truly live life on his own terms. “Yo Picasso” sold for 47.9 million dollars in 1989, making it one of the most expensive paintings ever sold at the time.

When did you reach your ‘Guffogg’ moment and separate from your father’s dreams, becoming Guffogg the artist rather than Guffogg the son taking over the family business? What did you create to conquer that moment?

Pablo Picasso, Yo Picasso, 1901, oil on canvas, 28 x 23 in.

Shane Guffogg: That is a big question. I will say I was practicing and trying to refine, or maybe the right word is define, my signature. I recall studying Rembrandt and Picasso's signatures, from their early years to their ends, looking closely at how they changed. I think I would have to say the self-portrait as Rembrandt was a turning point, even though I was only 18. The idea of putting my face into such a historical setting was a bold statement. But I think the next big step was in 1988, with my first ribbon painting On Your Mark and the group of paintings that followed it in quick succession. I signed the back of these paintings with charcoal to make sure my signature was embedded in the fabric of the canvas so that it could never be fully erased.

Guffogg’s first “ribbon” painting, On Your Mark, 1988

Acrylic, and oil on canvas, 18 x 20 in.

VC: Another thing you have in common with Picasso is peace. Although you are not a communist, Picasso was, and he spent years devoting himself to the party, going to peace conferences, painting imagery of his ideology, including his famous peace dove. Picasso’s father was known to paint pigeons. I think this is a fascinating connection, as you grew up on an exotic bird farm, and your family also had a connection to doves. Furthermore, in 1989, before the collapse of the Soviet Union, you went to Russia in a group for a one-month peace walk, sharing the words and thoughts of democracy. According to my files, in 1983, you made a dove painting; can you explain more of what your dove painting was all about?

Pablo Picasso, Dove of Peace, 1953

Shane Guffogg's Death of Dove, 1983

Shane Guffogg: We had a bird farm and by that, I mean pet birds – cockatiels, parakeets, lovebirds, and finches. We also had some morning doves. I remember walking into an aviary where the doves were and I could see one of them was not feeling well because its feathers were puffed out and its head was tucked away under its wing. The next day I went into the aviary and it was lying dead on the ground. The position in which it lied frozen and lifeless seemed symbolic of death itself. I was thinking a lot about the Cold War, as it was continuously being spoken of on the news. The dread that it was casting was like a neverending dark cloud. This dead bird was the embodiment of that for me, which was the opposite of Picasso's peace dove. I was very aware of his peace dove, which had been used all over the world. But I saw Picasso's dove as a nice picture that was not based in reality. This dead dove, which I painted in greys, was more truthful, I felt, about the ominous times we were living in.

I am going to wrap up my questions here. It’s been really interesting to note the parallels between your life and Picasso’s.

Stay tuned for more conversations

Victoria Chapman

Studio Manager

A very special thanks to Neville Guffogg for editing.

Note: all images shown in this email are (fair use) public domain